CONSERVE. PLAN. GROW.®

Choosing A Smart Investment Strategy

August 30, 2018

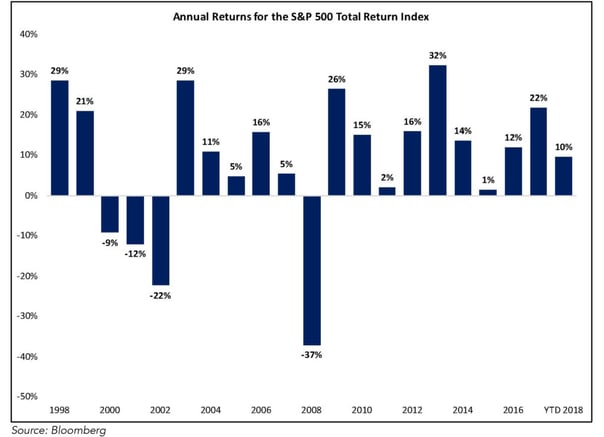

If you’ve ever looked at a graph of stock market returns, you might notice the similarities with an EKG. Lots of ups and downs.

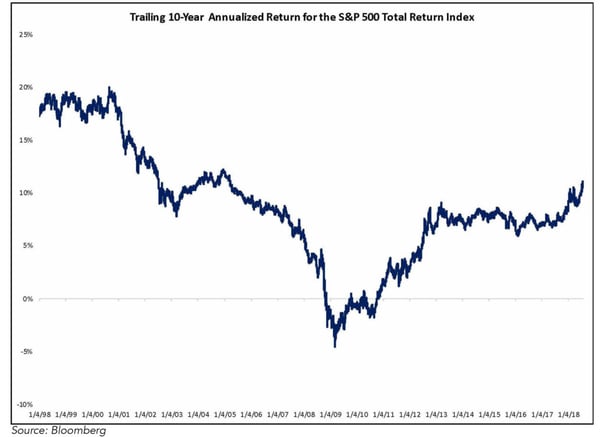

But overall, the trend is up. Over the long term, the stock market has delivered compounded annual rates of return of 8-10% per year. In order to achieve the long-term results that the market can deliver, however, you need to be able to ride out the turbulence.

When faced with volatility in portfolio values, people often do exactly the opposite of what they should do. When values go up, people start feeling better about the market and pile into stocks. When the market pulls back, they get scared and seek to get out. The result of such emotion-driven investment decisions is to buy high and sell low, the opposite of what we want to accomplish as investors.

Smart investing requires a strategy that takes the emotion out of investing. We need an investment strategy that accomplishes both our short-term and long-term goals and enables us to stick with our decisions during all market conditions.

Smart Asset Allocation

An investment strategy starts with your asset allocation – what percentage of the portfolio you invest in stocks, bonds, and cash. A smart allocation is one in which your exposure to each asset class is “right-sized” relative to your objectives, your liquidity (income) needs, and your personal tolerance to “volatility risk.”

Volatility risk refers to price swings in the value of an asset. The price of a highly volatile asset can change dramatically in either direction over a short period of time. Volatility risk is not the same as risk of loss. Volatility risk only becomes a risk of loss when one decides to or is forced to sell (liquidate) the assets. Your “capacity” to tolerate volatility (ride out the downturns until the market returns) is thus strongly tied to your time horizon. If you plan to sell an asset (or think you might need to sell an asset) in the short-term (~12-36 months), you might not have the capacity to ride out a downturn.

Asset Classes Vary in Volatility

Cash: The least volatile of the 3 main asset classes, cash or cash equivalents (Money Market funds, CDs, US Treasury Bills, and other short-term instruments with a duration of 3-months or less) generate low returns but are not subject to material changes in valuation. The level of cash you should keep in your investment or savings account depends on your need for short-term liquidity. Cash is a smart place to hold funds that you plan to use in the next 6 to 12 months, such as for living expenses, large purchases, or educational expenses. It is prudent to keep those funds in a cash and cash-equivalent investments which will not materially change in value so that the money will be there when you need it and will not drop in value in the meantime.

Bonds: Bonds are more volatile than cash but less volatile than stocks. A balanced, well-diversified bond portfolio should generate modest returns with a small to moderate risk of volatility (historical long-term fixed income returns have averaged 4-5% per annum, but that is more difficult to achieve in the current low interest rate environment). Bonds are a smart allocation for money you plan to spend within the next 1- 5 years because the value is relatively stable and the income is predictable.

Stocks: Stocks are the most volatile of the 3 asset classes, but also are expected to produce the highest annualized returns over the long-term. Stocks are an appropriate asset in which to invest funds that you don’t plan (or have) to use for 5+ years because if there is a dramatic decline in the value of the stock portfolio, you will want time to ride out the recovery. You don’t want to be forced to sell out of stocks when the value is down. A good example to demonstrate this was the dramatic decline in the stock market in 2008.

An investor who bought an S&P 500 index fund at the start of the 2008 would have seen the value of his/her investment drop by 38% by year-end (intra-year, the index declined 49% in 2008). It took 18 months for the stock market to return to its pre-drop levels. If the investor held on to stocks for five years after the drop (12/31/08 – 12/31/13), he/she would have earned average annual returns of about 18% per year. Seen from an even longer-term perspective, the 10-year annualized return at the end of 2013 was 7.4%. Despite big swings in valuation during that decade, the investor who remained invested would have earned an average 7.4% compounded annual return from 2004 through 2013.

Now back to the notion of what constitutes a “smart” allocation. From my perspective as a financial planner, the starting point is the investor’s time horizon, which is the biggest determinant of an investor’s capacity to handle volatility risk. The first question you should answer is “what are your distribution needs from this portfolio over the next 12 months, in the next 1 to 5 years, and beyond the next 5 years?” The starting “base case” would be to allocate 12 months of planned distributions to cash equivalents, the next 5 years of planned distributions to bonds, and the balance to stocks. For example, if planned yearly distributions were 5% of the account value, the “base case” allocation would be 5% cash, 25% bonds, and 70% stocks.

After establishing the base case, you should layer in other factors that influence for your tolerance for volatility risk:

- What is your primary objective for the account—preservation of capital; generation of income; growth of principal; or balance between income and growth of capital? Make sure that the expected returns of the balanced portfolio are in line with your goals.

- What is your personal/ emotional tolerance for swings in portfolio value? How much of a decline in portfolio value can you handle psychologically before you want to “throw in the towel”? The balanced portfolio you choose should have a historic standard deviation that does not exceed your boundaries.

A smart investment strategy is one which allows you to accomplish your goals and at the same time balance volatility risk appropriately so that you can stick with your strategy through the good times, the bad times, and everything in between. Periodic rebalancing of the account (returning to your strategic allocation targets) ensures that you take the emotion out of investing and capitalize on short-term volatility. Because you are methodically selling out of what has done well and buying into what has underperformed when you rebalance, chances are you’ll be “buying low and selling high,” the key to successful investing.

Disclosure

This article does not represent a specific investment recommendation. No client or prospective client should assume that the above information serves as the receipt of, or a substitute for, personalized individual advice from The Fiduciary Group which can only be provided through a formal advisory relationship. Clients of the firm who have specific questions should contact their The Fiduciary Group advisor. All other inquiries, including a potential advisory relationship with The Fiduciary Group, can be directed here.